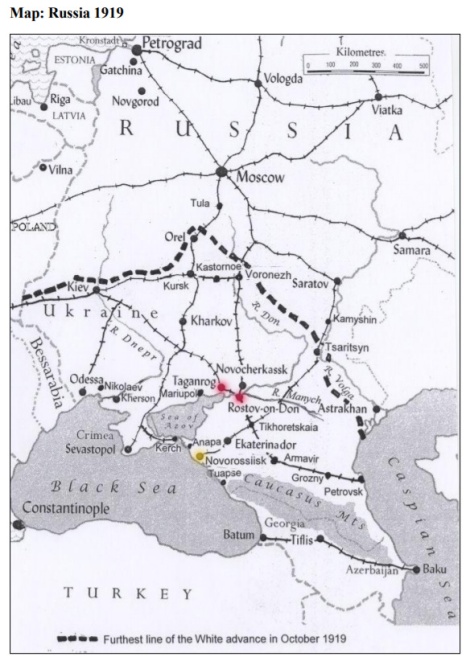

Here’s a map to remind you where we are. Russia 1919. Adapted from Kapisto’s dissertation (Kopisto, p.194).

The distance from Taganrog to Rostov is about sixty miles but it took us three and a half days to get there. When we were in Taganrog we saw some old cannon balls buried in the walls of the hospital which were used by our fleet in the bombardment of Taganrog during the Crimea War…

Because why wouldn’t you be a tourist while you are in full flight with the Red Army on your heels?Granddad’s journey from Taganrog began on January 2nd and took until January 6th. Taganrog fell on January 4th. Rostov would fall on January 9th (Smith, Chapter 17, 2010).

We arrived at Rostov at 6pm on Sunday 6th Jan. 1920 & left at 8pm on the same date.

As mentioned my granddad was with the RAF whose 47 squadron was stationed in South Russia. It was B Flight of the 47th that were in the same area as my granddad at this point and we looked a little at their stort last week by way of Marion Aten’s part-fact, part -fiction book, Last Train Over Rostov Bridge. A factual version of the story of B Flight’s hasty retreat from Taganrog is recounted in Damien Wrights’ book Churchill’s Secret War and explains how it might take three and a half days to travel this distance. I say ‘version’ as there are still contradictions with other accounts and the dates as always are vague. Bear in mind the following occurs in the run up to New Years Day 1920 while granddad was still in Taganrog.

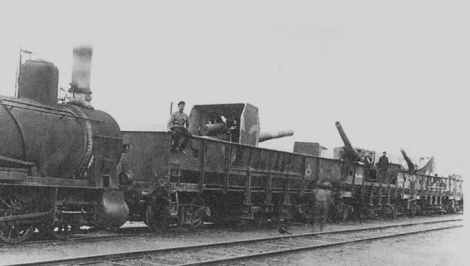

White Russian armoured train c. 1919. Image available at http://warfarehistorian.blogspot.ie/ [accessed 30/12/2017].

B Flight had left Taganrog and were about 20km from Rostov on their own train when they came across another train, its boiler broken, with British officers on board. The dashing Charles Dance lookalike General Wrangel had sent a train from Rostov for the abandoned British with General Holman on board. That train had broken down too so gung-ho General Holman, a soldier who, contrary to a lot of the officer class, preferred to be at the front shooting at things and had already offered to take a train and blow up the bridge at Rostov (Kinvig, p.307), relieved B Flight of their engine to speed his officers to safety. B Flights’ train was eventually rescued by a White Russian Officer who towed it, presumably with an engine, to Rostov. As they approached they could see Rostov Bridge teeming with refugees fleeing south.*

*Wright says here they were fleeing White soldiers though it was the Red Army that were advancing and the Whites were also fleeing. I imagine though, for many both armies were worth avoiding.

Rostov was deserted, houses and shops boarded up but the hospital jammed with thousands of typhus sufferers. While the dates are not included in this account it is known that B Flight were looking for transport out of Rostov on New Years day 1920 when my granddad was still preparing to leave Taganrog 70km back up the line. They left a couple of days later, abandoning their train and all their supplies and walking eleven miles and across the bridge to a waiting Military Mission train. They could not set fire to their own train because the press of refugees was so great and so it had to be left for the Red Army. All along the way refugees clutched at them, weeping and thrusting their children at them begging them to take them to safety.

Atens’ book expands on this misery…

The misery I had seen aboard the trains, heart-rending though it was was nothing compared to that of the road. Singly and together scores of refugees lay dying and dead from the cold, starvation, typhus, small pox or all of them combined. I passed a mother with two children huddled up against her like animals, for the last warmth she could give;some passerby, taking pity, had tossed an oriental rug over them and then gone on his way. A demented woman sat on the road side counting and recounting her fingers. The weather had turned more sharply cold, and adults and children walked along side or rode on rough carts, the ancient buggies, the rusted sleighs, with frostbitten feet and fingers (Aten, 1961).

This account of B Flights’ escape as the Bolshevik Army encircled the city paints a picture of a city yet it would not fall until the 6th when my granddad arrived and hurriedly left again. It was on the 9th of January, you will remember from a previous post (which you can read here) that two British soldiers were captured and brutally killed at Rostov by the Red Army having been abandoned by White Russian soldiers (Wright, p.420).

My granddad, in keeping with the rest of the diary, includes little detail of the mass retreat but he does give us a thumbnail sketch of a scene that must have been all too familiar in those times and which in a few lines conveys the horror of it.

We arrived at Rostov at 6pm on Sunday 6th Jan. 1920 & left at 8pm on the same date. Just outside Rostov station we saw two men hanging from a tree who had been hanged by the Russian army for distributing Bolshevik propaganda. While one of them was being hanged his brains were blown out by a Russian officer. It was a terrible sight to see.

The Red Terror was a program of executions carried out by the Red Army, officially in 1918 but extending for the whole period of the Civil War. These executions were aimed at all political enemies of the Bolsheviks. In effect I imagine it was a carte blanche for everyone and anyone to kill anyone they didn’t like. The regime afterwards would blame the 100,000 plus executions (Lincoln, p.384) on over-excited peasants (Melgunoff, 1927). There was of course a corresponding White Terror. That is all to say hangings and shootings must have been fairly common sights and at this point a standard response by whoever had the upper hand to punish or pacify any sort of wrong doing. It led unsurprisingly to retaliatory acts of vengeance by victorious troops too, in some cases the cause and effect only being hours apart, as we will shortly see.

General Mamontov leader of the Don Cossacks in 1919. He would die of typhus in Ekaterinoda in February 1920. Available at https://www.flickr.com/photos/ruscadet/5330790598/in/album-72157625637170319/ [accessed 30/12/2017].

Rostov was in Don Cossack territory where the Volunteer Army had been formed and The Don Cossacks under a strong leader, General Mamontov, were allied to the White Army (Occleshaw, p.56) (you will remember the dashing General Wrangel fought with the Kuban Cossacks from the the area south of the Don) but different factions fought for different reasons and while the Cossacks were fearsome fighters and anti-Bolsheviks, they detested peasants and possessing an independent spirit they tended to fight only for their own beliefs or territories. There were always tensions between the the Cossacks and the ex-Imperial White Army officers which were by now at breaking point (Kopisto, p.153). The Don Cossacks were demoralised having suffered severe defeat in late 1919 after which General Mamontov had been removed by Denikin which served to alienate the Cossack troops (Kinvig, 305, 306). These were possibly elements in what happened next.

About two hours after we left Rostov the Cossack Brigade which was to defend the town turned Bolshevik and murdered all the loyal Russian soldiers & handed the town over to the Bolshies.

I have not found any particular reports of Cossacks turning Bolshevik at Rostov yet though in the climate it is certainly plausible and it was the Don Cossacks rebelling at Orel that helped put an end to a string of White victories and cut short Denikins advance on Moscow. However the Cossacks would suffer under the Soviet regime and there would be Cossacks-who were much admired by British General Holman-evacuated at Novorossiysk by the British. Despite this Cossack brigade rebellion and the head-long Red Army advance, the line at Rostov along the Don River would hold for a further three months, months which my granddad would spend at a chaotic Novorossiysk (Kinvig, p.309).

Next Week:Ekaterinoda and The Green Guards.

Infantry of the Don Army on the march in Rostov-on-Don, May. 1919. Available https://dambiev.livejournal.com/907475.html [accessed 30/12/2017].

Ash, L., (2017), Death Island:Britain’s Concentration Camp in Russia, October 19th on the BBC, [online], available at http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-41271418 [accessed 30/12/2017].

Aten, M., Orrmont, A., (2011), Last Train Over Rostov Bridge, revised ed., London:Thin Red Line Publishing.

Kopisto, L. (2011), British Intervention in the Russian Civil War, Helsinki:Helsinki University, [online], available at https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/26041/thebriti.pdf [accessed 30/12/2017].

Kinvig, C., (2006), Churchill’s Crusade:The British Invasion of Russia 1918-1920

Lincoln, W. B., (1989), Red Victory: A History of the Russian Civil War, New York: Simon & Schuster.

Melgunoff, S., (1927), Record of the Red Terror, [online], available at http://www.paulbogdanor.com/left/soviet/redterror.pdf [accessed 30/12/2017].

Occleshaw, M., (2006), Dances in Deep Shadows:Britian’s Clandestine War in Russia 1917-1920, London:Constable & Robinson.

Smith, J., T., (2010), Gone to Russia to Fight: The RAF in South Russia 1918-1920, London:Amberley Publishing.

Wright, D., (2017), Churchill’s Secret War:British & Commonwealth Intervention in South Russia 1918-1920, Solihull:Helion Publishing.

Such a scary and sad time, though I imagine they were too busy staying alive and getting away to be scared. The things your grandad saw must have stayed with him all his life. Your painting is so emotive.

LikeLiked by 1 person

They must have but I dont think he talked about them. The account of it is all wehave really. And youre right…when people are going through things they are intent on surviving…it seems awful only when we have the leisure to think about being in such times.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m reading Dr Zhivago and I’ve almost reached this time. Everyone is afraid of everyone else and people are being killed for little reason. I came across the first mention of the greens this morning.

The painting is wonderful. It makes me very grateful that I live when and where I do.

Your Granddad must have been terrified by now. I know his words don’t show it, but he must have been very aware of what would happen if he was captured.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I must read Zhivago myself I think!There is a lot mention of the Green Guards in his diary for the next few entries so next week will be on them. They seem to be the main aggressors in the Caucasus at this point. Thanks for the kind words about the painting. I think more than words they can convey a feeling of the time.

And yes he must have been scared I suppose. Or maybe when its is so chaotic on the ground, though various images are presenting themselves, one is just living in the present and getting through. It must be hard to grasp the enormity when you are in it. A friend of mine was in Sri Lanka when the Tsunami hit in 2004 and though she was on the beach and she ran from the wave and though she saw bodies, had to travel inland, and helped with the initial rescue efforts, she was relying on us back home to tell her what was going on. Bizarre.

LikeLike

Yes, when you’re in it, I expect that information is lacking.

LikeLiked by 1 person