We started retreating at 3pm on New Years Day and we took all our Bolshie prisoners with us. I was one of the advance guard and on the march to the station during which we were up to our knees in snow we commandeered all sleigh and horse traffic at the bayonet point.

98 years ago today my granddad was packing up, exploding bombs and setting aeroplanes alight in the depths of the South Russian winter as the Bolshevik army were bearing down on the British Military Mission Headquarters at Taganrog. The next day the retreat proper began. For the British that is. The White Army had fled earlier at the first whiff of the Red Army (Wright, p.420).

This entry is the first mention of Bolshevik prisoners. The British were officially not meant to be fighting, or, I imagine, taking prisoners but the reality in a chaotic situation was different. As we know RAF Squadron 47 took part in air battles while British tank and artillery instructors ended up at the front. Taking prisoners then may have been unavoidable. And whereas the Whites and the Reds had little compunction executing their enemies the British probably dealt with things differently. A recent article on the BBC website tells of a concentration camp set up by the British in North Russia during this period. Mudyug Island near Arkhangelsk housed a 1000 prisoners at one point (Ash, 2017) but it is unlikely my granddad’s prisoners ended up there I suppose. In the ensuing 3 months chaos of evacuation is hard to imagine the British hanging onto their prisoners. They would have had to execute or free them. Or hand them over to the White forces which would be extant until June of 1920.

- This is a fairly posh Russian painted sleigh from the early 19th century. It’s not beyond belief that there were a few posh sleighs complete with aristocrats in them knocking around but I imagine the majority of sleighs would be more workaday. This is a mere €27,000 to buy if you are interested. Image available at https://www.1stdibs.com/furniture/more-furniture-collectibles/collectibles-curiosities/sports-equipment-memorabilia/?q=sleigh [accessed 30/12/2017].

The British Military Mission HQ at Taganrog was more than likely where the military airbase is now, some four miles north-west of Taganrog centre. Who can imagine what that four mile wade through the snow was like in the bitter cold and dark with another 450km to cover to get to safety at Novorossiysk?It was possibly more scary for sleigh and cart drivers than for the soldiers. The British were often regarded as national heroes in White held cities but rural areas were less enthusiastic and often even ignorant of the intervention (Kapisto, p.136) so as refugees from all points north continued to pour through the area trying to reach Novorossiysk, friendly responses would not have been guaranteed. Many must have been armed to some degree and it would have been impossible to know who was who in the dark so nerves on all sides would have been stretched to the limit.

This type of sleigh may have been more common. Horse-drawn lumber sleigh, Murmansk, North Russia, 1919. British Army Official photographer. Image © IWM (Q 16598) available at http://media.iwm.org.uk/ciim5/268/995/large_000000.jpg?action=d&cat=photographs [accessed 30/12/2017].

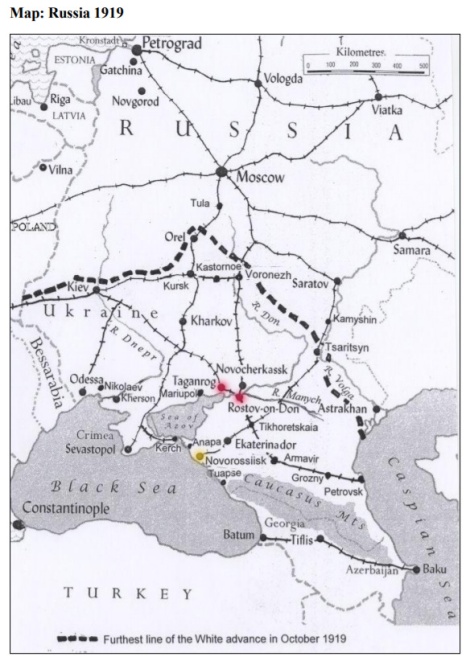

As mentioned before the Russian Civil War depended on the railway and is often called the Railway War. This must have been doubly true in winter when deep snow would have made the steppe unnavigable. While Taganrog was in certain danger, it was Rostov-on-Don 70km to the east that was the bottleneck everyone would have to pass through. From Taganrog a theoretical escape might have been possible south-west to the Crimea and indeed A Flight had escaped that way between Christmas and New Year arriving at Sevastopol on January 4th. A Flights’ retreat was plagued with Bolshevik saboteurs breaking up the lines to the extent that sometimes, in cartoon-like fashion, A Flight would have to rip up track they had just passed to replace missing areas ahead. At one point they were pursued by a Red Army armoured train but managed to steam out of range of its guns (Wright, p.426). By the time of my granddad’s retreat, a week after A Flight passed through,the Bolsheviks would gain control in the area leaving Novorossiysk as the only possible escape route (Kinvig, 310).

Here’s a map to remind you where we are. Russia 1919. Adapted from Kapisto’s dissertation (Kopisto, p.194).

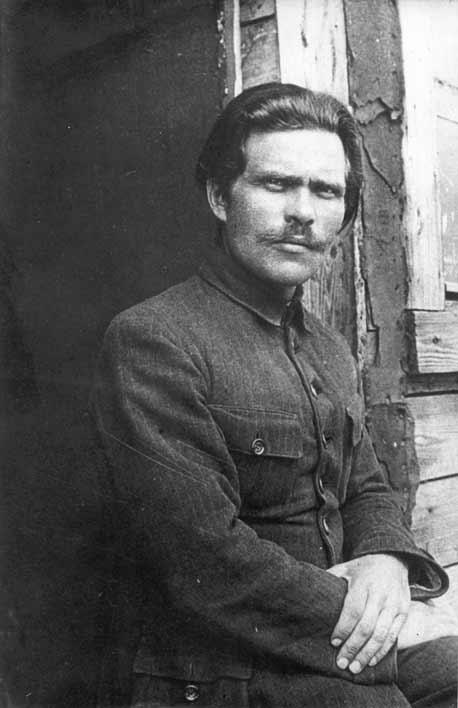

It was in this area of the Ukraine, between Dnepropetrovsk and Mariupol, that the anarchist peasant group-which you may remember as the Black Army-also known as the Independent Army of the Ukraine and led by the charismatic Nestor Makhno had been marauding and attacking the Whites in the autumn of 1919 but the Whites had quelled them only to open up the region to the Red Army (Kopisto, p.151-152) typical of the knock on effect on war in this fragmented region.

Nestor Ivanovich Makhno (1888-1934) in the camp for displaced persons in Romania 1921. Available at

After that night time trek through the snow, when they reached Taganrog station (incidentally still the same building today as it was then) there were, unsurprisingly, no trains available.

When we got to Taganrog station which was a four mile walk, we had to commandeer a train.

The surprise is they got a train at all. Whose train was it though?In an account of B Flights retreat on the same route, which we will look at next week, General Holman commandeers their train to rescue British officers that were stuck on a broken train 15km out of Rostov. Among these officers was Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Maund, head of the RAF training mission, who claimed incorrectly, in Marion Atens book at least, to be the last train out of Taganrog (Aten, p.)) The account confusingly mentions that Holman is also rescuing officers stuck at Taganrog a further 55km away (Wright, p.420). I thought that maybe this meant that the broken train carrying the British officers was meant to make a number of trips up and down the line. There were only around 600 British Mission men in South Russia at this point (Kinvig, p.313) but its possible the trains did not have great capacity or they were filled with refugees and stores so the train that Holman was on could possibly have been the train my granddad is referring to when he says ‘we had to commandeer’ a train, ‘we’ being the British Army. But I looked a little further.

There is a book I haven’t mentioned because I haven’t read it and I haven’t read it because it is often described as being unreliable as it is part fiction. Last Train Over Rostov Bridge was co-written by Lieutenant Marion Aten an American volunteer with B Flight who were retreating along the same route as my granddad only some days earlier. Damien Wright says Aten’s book, published in 1961, mixes in large passages of fiction with fact and suggests much of it must be taken with a big pinch of salt (Wright, p. 406-407). However the revised edition of 2011 contains notes from a Major George Treloar who was also in South Russia at the time and was, like granddad, one of the last out of Taganrog. Treloar says he did not see Holman at Taganrog though he may have passed through. Treloar states he did not get out of Taganrog until some days after New Years, but that there was no panic among those left behind, about 100 men who had with them with most of the British Mission Archives. He also says it was (the dashing) General Wrangel who organised the trains between Rostov and Taganrog, directing two trains, ten hours a part to collect the remainder of the British Mission. I think it must have been one of these trains that granddad was on. So you see General Wrangel not only looked dashing he was dashing. And I like to think he played a small part in enabling my eventual existence…

Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel (Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel) protector of my genes c.1920. Author unknown. Available at https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e3/Pyotr_Wrangel%2C_portrait_medium.jpg [accessed 30/12/2017].

We left Taganrog at 5am on Friday 2nd Jan. 1920. The distance from Taganrog to Rostov is about sixty miles but it took us three and a half days to get there.

I will include a description from Aten’s book of the landscape my granddad passed through on the way to Rostov. As David Footmans’ blurb says on the cover, Aten’s books provides something academic work does not:the feel and the smell of actual participation in human struggle and tragedy.

The trip to Rostov was another exercise in Jobian patience. The line crept forward, a mile an hour, sometimes only two or three miles in a morning, an afternoon. When we passed a station it was necessary to keep our engine jammed tight against the rear of the train ahead;otherwise refugee coaches, waiting for a box-car length of space to pounce on, would cut in line.

Seaward, three hundred yards at this point, lay the Azov, cold and bleak and fog shrouded. The wagon road on the landward side of the tracks was black with refugees, soldiers and mounted Cossacks on patrol. The civilians and military travelled in carts, sleighs, on horse and on foot. Both were typhus-ridden, and bodies, some stripped of their outer clothing, dotted the landscape.

On our third day out the staff cars began passing on the open track. Drawn-faced officers stood looking dully out of the windows of coaches clicking by at express train speed. Obviously Taganrog was being evacuated. One string of trains had palatial dining cars in which an orchestra and jugglers entertained a fat general with white, close-cropped hair. In cinema dramas to come of the Civil War, I thought, such a scene would undoubtedly figure.

Next Week:Rostov & ‘A Terrible Sight.’

Further References and Reading

Ash, L., (2017), Death Island:Britain’s Concentration Camp in Russia, October 19th on the BBC, [online], available at http://www.bb.c.com/news/magazine-41271418 [accessed 30/12/2017].

Aten, M., Orrmont, A., (2011), Last Train Over Rostov Bridge, revised ed., London:Thin Red Line Publishing.

Kopisto, L.. (2011), British Intervention in the Russian Civil War, Helsinki:Helsinki University, [online], available at https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/26041/thebriti.pdf [accessed 30/12/2017].

Kinvig, C., (2006), Churchill’s Crusade:The British Invasion of Russia 1918-1920

Lincoln, W. B., (1989), Red Victory: A History of the Russian Civil War, New York: Simon & Schuster.

Melgunoff, S., (1927), Record of the Red Terror, [online], available at http://www.paulbogdanor.com/left/soviet/redterror.pdf [accessed 30/12/2017].

Occleshaw, M., (2006), Dances in Deep Shadows:Britian’s Clandestine War in Russia 1917-1920, London:Constable & Robinson.

Wright, D., (2017), Churchill’s Secret War:British & Commonwealth Intervention in South Russia 1918-1920, Solihull:Helion Publishing.

My goodness, this is exciting. This reminds me of the bits of Dr Zhivago I’ve seen. I’m sure they spend a fair bit of the film travelling through the snow in trains full of soldiers.

I bet there was some panic, though. They must have known by then that they weren’t going to be treated well if they were captured.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks April..thats good to hear, I thought this post might have too much info which would kill the excitement…You would think there would be panic wouldn’t you?I panic even if I think I am late for something and theres no army after me!Then again they were soldiers and trained and British. The stiff upper lip carried people a long way. Look at that other Scott in the Antractic. And maybe it was too cold to panic?Maybe all their energy was taken keeping warm?Or the panic wasnt overt because its hard to run up and down in snow 😀 I think I will do a small mid week post on the weather. My granddad too, I am getting to know him a bit, didn’t seem to be the type to panic at all. An essentialist my father describes him as. Thanks again April.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s a lot to be said for a stiff upper lip, but I suspect it was the training that was most useful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is and yes, training I imagine would do the trick…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I forgot to say that your picture is very atmospheric and really sets the scene.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great..exactly my intention. With these long posts with a lot of information it can be hard to visualize a scene…pictures help so much to crystallize it all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It IS exciting stuff. I think I’m a little in love with General Wangle. Love your painting, can feel the cold and trudging through the snow in it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Ta Fraggle…yes I think Im in love with Wrangel too!! 😀 The photos of him are cool, he loved his style…Ill post up a few in a day or two.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cool, look forward to more sartorial elegance!

LikeLiked by 1 person

General Wrangel does look very distinquished, though most old photos of people are taken in very formal poses. Like they had a rod up their backs 🙂 Love the painting you did Clare. Still think this an amazing journey of your grandfather’s war experience that you are sharing!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Suz..yes you are right about the way the took photos…but when you see Wrangel along side other you know he was a total dandy…also he seems to be about 7 foot tall! Thanks for coming with us to Russia x

LikeLiked by 1 person

A total dandy, I love it. Another word for eye candy 😉 x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hhahaha!Eye candy dandy…I think that will have to be included in the Wrangel post title 😀

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m amazed, I must say. Seldom do I come across a blog that’s both equally educative and interesting, and without a doubt, you’ve hit the nail on the head. The problem is something that too few people are speaking intelligently about. Now i’m very happy I came across this during my hunt for something regarding this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yhanks you Stefan, thats good to hear!

LikeLike

Pingback: History Repeats – Ukraine & South Russia | From Dublin to South Russia & Return Journey·